What is nature? Is it untouched beauty? Two questions that conjures a third: What is this so-called untouched beauty? Something that is unsullied? Showing no obvious signs of damage? In exceptionally good condition? Unadulterated? Pristine? And who or what should not have touched it in order for it to qualify as such? At this point in the history of planet earth, are there untouched areas of nature that really exist?

These are some of the questions that crept into my brain after seeing Barösund 1870 –> 2023, one of two inaugural exhibitions focusing on the environment at Chappe—the new museum of modern art in Ekenäs / Tammisaari, Finland—a.k.a. Art House By The Sea.

Barösund 1870 –> 2023 happens to be the inaugural version of what will be an ongoing series of exhibitions. Here, four contemporary artists responded to Munsterhjelm’s Eventide in Barösund, which is from the museum founder’s collection by producing works that varied greatly in terms of media and scale. While Panu Ruotsalo’s trio of large, liquidy paintings—said to refer to air, water and earth—that float between abstraction and representation, Ahmed Alalousi and Sandra Kantanen resorted to contributing photographic works.

What surprises is these artists’ take on the Munsterhjelm theme. Not only have they conceived more traditional representations of the local landscape, but all of their contributions emphasise a triad of images. So, we have Ruotsalo’s three canvases echoing Alalousi’s three photos, which then parallel Kantanen’s trio of digitally manipulated images.

Mind you, differences do exist. While Alalousi’s unframed and similarly sized pictures are accompanied by a video, only two of Kantanen’s variably sized and framed pieces are backed by her mural. The third, on the other hand, hangs nearby on an adjacent, and otherwise bare, white wall. With friends like these, it’s not hard to see why Katerina Reuter‘s lonely scene stands out.

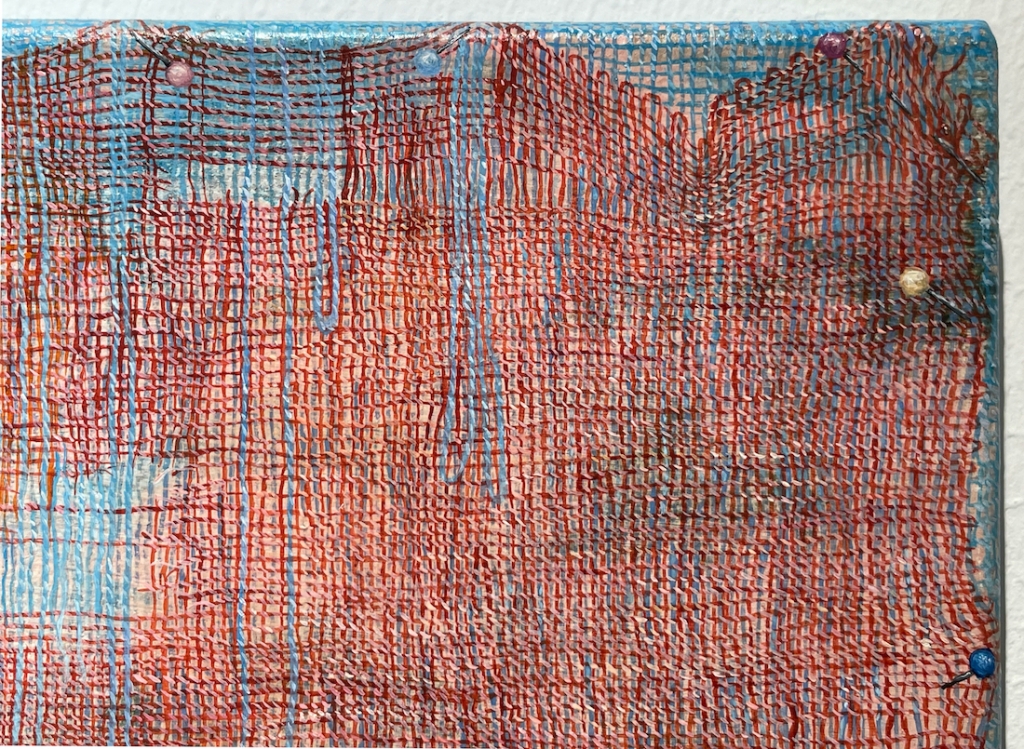

She has, first and foremost, limited herself to producing a single canvas—a copy of Munsterhjelm’s scene—to create a relationship that is most poetic. Notice the virtually identical size and structure of the two works, for example. Notice, too, that she has used map pins to impose a screen between her copy of Munsterhjelm’s landscape and us—an irregular and variegated open weave fabric, which is still in the making.

And who is it that’s making it? Well it’s a collection of birds, spiders and moths, butterflies, dragonflies, beetles and larvae. It’s made up fragments of thread, red, blue and gold, and spider’s web. One large butterfly has also managed to take hold of a loose thread. It appears to have started fraying the tiny ship’s sail.

The way that Reuter has combined and layered imagery in her take on Munsterhjelm’s canvas causes multiple multiple meanings to be considered. Is the mesh being created by these creatures an act of reclamation, for instance? Could it be an attempt to block out an idealised, hackneyed and discriminative depiction of the landscape, to quash empty symbolism by replacing it with a dose of reality—their reality?

Reuter’s title also speaks of faithfulness. By referring to Penelope, the ancient queen of Ithaca, it reminds us that she remained faithful to her husband Odysseus, the hero of the Odyssey. It is believed that her name is also linked to a type of bird and a weaver. Wikipedia notes that this weaver is cunning, which makes it difficult to ascertain what drives them.

Perhaps the best thing about this work is its sense of playfulness, the artist’s technical skill and use of colour, the idea of using a scrim, which a adds a dreamy quality, as it can in the theatre, or reveal things in a new light, such as the qualities of spaces manifested by the artist Robert Irwin in his installations. It’s also possible to see this overlay as a reference to other forms of weaving. Humans use to weave by hand and still do, but the artist’s 19th century linen canvas was likely machine made. Perhaps birds and spiders, which have been weaving their nests and webs for eons, influenced what we humans do. Such affiliations also come across as a correspondence, a bond, a type of fidelity.

And getting back to that initial question: What is nature? It looks as if it’s more intertwined and more ‘touched’ than untouched and—considering climate cycles, our effects on the planet, and/or the threat of mass extinction (pick your theory)—subject to ongoing, and sometimes very dramatic, change.

Barösund 1870 –> 2023, Chappe, Ekenäs / Tammisaari, Finland (16 April — 3 September 2023)

Also, now showing:

Katerina Reuter: Black Crow Blues, EMMA — Espoo Museum of Modern Art, Espoo, Finland (4 October 2023 — 28 January 2024)

Photo: Thus Gus (unless specified otherwise)